And No, You are Not Going to “Blow Away” your Coffee’s Flavors

Airflow in coffee roasting has always been somewhat misunderstood. Many newer roasters worry they will “push out” flavors if they turn the fan on too high, while others underplay its importance altogether.

The reality is much more practical: airflow is primarily about creating a clean, stable roasting environment. Let’s break this down across 5 important areas.

Why You Need Airflow When Roasting Coffee

The roasting drum is an incredibly dynamic environment — coffee beans are under physical, chemical, and thermal transformation all at once. Airflow is the invisible hand that stabilizes this chaotic process.

Removing debris and chaff:

During roasting, coffee beans shed their thin outer husk known as chaff. Without proper airflow, this lightweight material floats inside the drum or burns against hot surfaces, creating smoky, bitter flavors in the final cup. Good airflow ensures that chaff is efficiently pulled away and deposited into the collector, keeping both the roaster and the flavor profile clean.

[Fig 1.] Green and roasted coffee contains a surprising amount of debris, which needs to be removed from the final roasted product.

Managing smoke and byproducts:

As beans reach higher temperatures in development, they emit smoke and volatile organic compounds. These gases, if trapped inside the drum, can settle back onto the beans, muting brightness and adding unwanted ashy or harsh notes. Airflow acts as a flushing system, constantly replacing the roasting chamber atmosphere with cleaner air, which preserves clarity in the cup.

[Fig 2.] The roasting process emits smoke and other gases that can taint the coffee’s flavor and do harm to the human body. No matter the roasting batch size, it is crucial to make sure that the exhaust is properly managed.

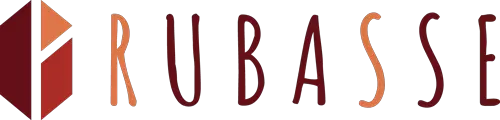

A method of heat transfer:

For a wide range of roasting equipment such as the traditional drum roaster, “popcorn” roasters, and modern “hot air” or “fluid bed” roasters, airflow also plays the role as the medium that transfers the necessary heat energy onto the coffee for the roasting to happen.

Important airflow parameters that may affect the roasting are:

(1) The temperature of the air, and

(2) The amount of air that passed through the bean batch (the flow volume)

By altering the burner’s output, the amount of airflow, and the churning/mixing of the beans (usually by adjusting drum speed), roasters can create different roasting conditions such as:

- High air temperature, low airflow volume through beans

- Low air temperature, high airflow volume through beans

…etc, where each different roasting condition gives different flavor results (even on the same green coffee).

[Fig 3.] Hot air in a hot air coffee roaster is forcefully blown through the roasting bean pile, floating the beans and transferring the heat necessary for roasting simultaneously. Photo excerpted from https://www.newordercoffee.com/

Designing Airflow for Effective Debris Removal

Beyond simply “turning the fan on,” the efficiency of airflow depends heavily on how a roaster is designed to channel it. Coffee roasting machines vary, but certain principles consistently support effective chaff and smoke removal:

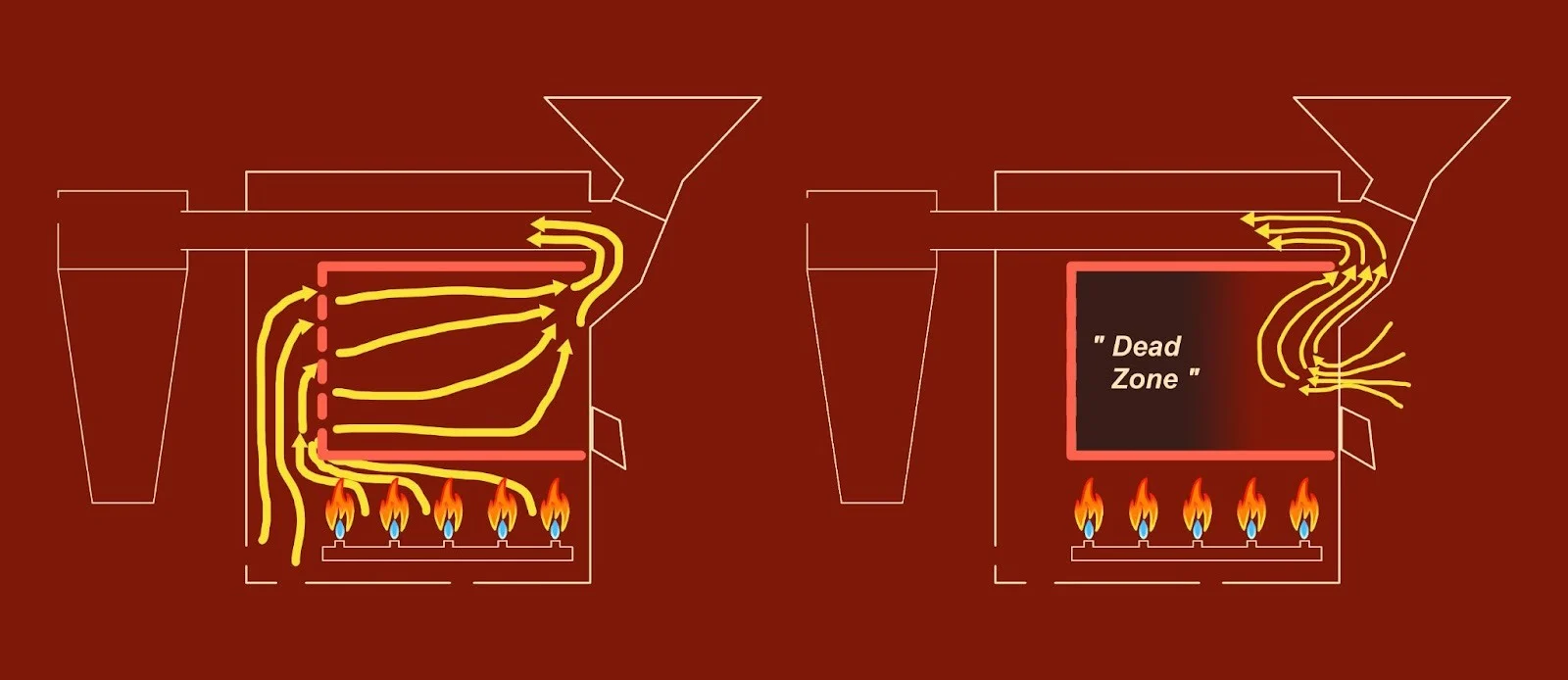

Clear direction of airflow:

Good designs establish a deliberate intake and exhaust pathway.

Fresh air is usually drawn in near the burner or drum housing, swept across the rotating drum chamber, and then expelled toward a chaff collector and exhaust duct.

This ensures that airflow passes through the bean mass, carrying debris out in a single, consistent direction instead of letting it circulate aimlessly.

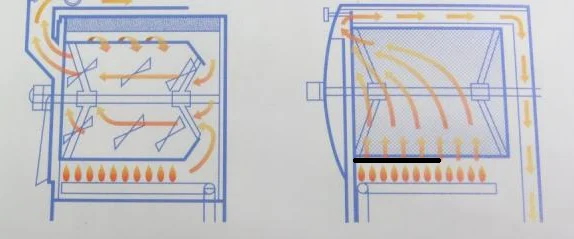

[Fig 4.] The direction of airflow in the commonly seen drum roaster. The left one has a solid drum while the right one has a perforated drum (this configuration is sometimes known as the “direct fire” roasting machine configuration”).

No “Dead Zone”s (For Airflow):

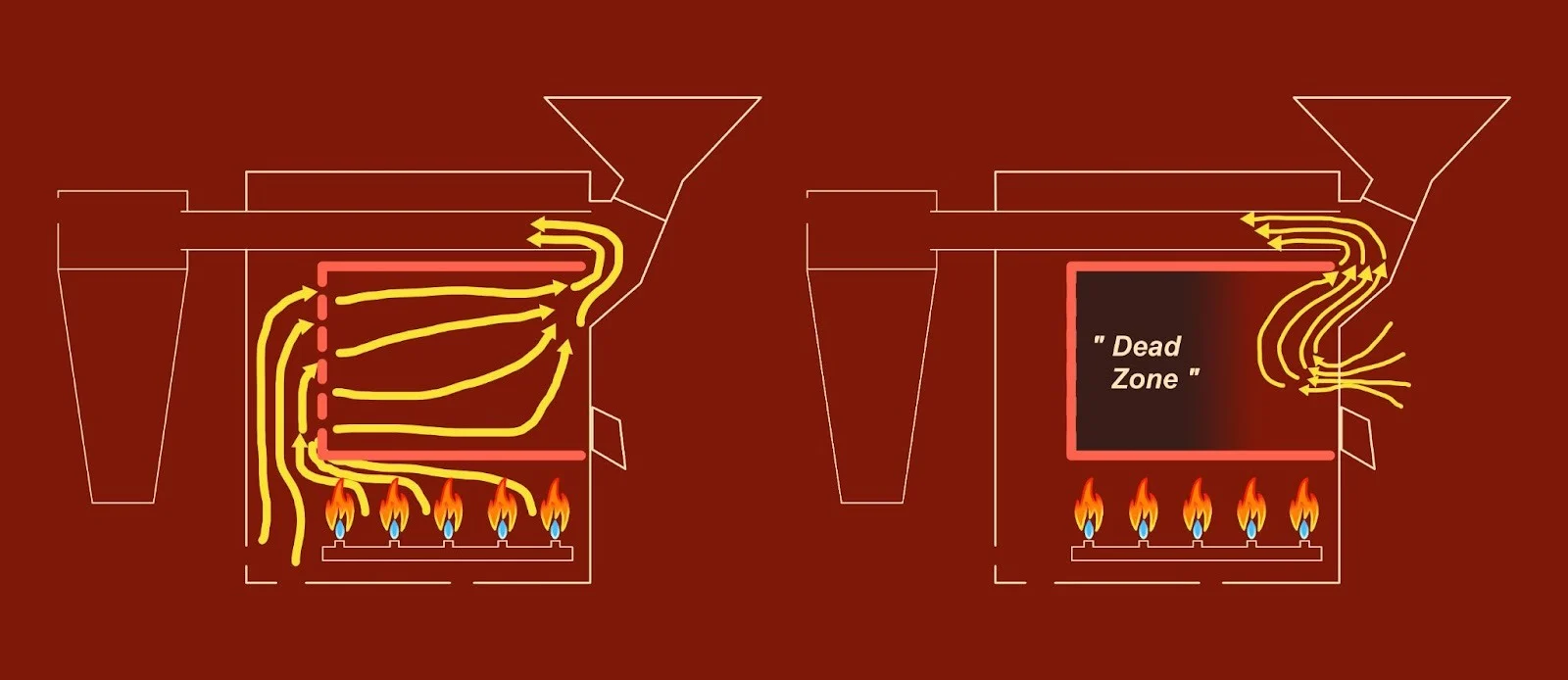

Chaff removal relies on consistent and smooth airflow within the roasting environment.

If areas of “air stagnation” form, chaff can fall back onto hot surfaces or sneak into cracks and bearings. Well-designed airflow avoids dead zones, creating a smooth current that keeps everything moving toward the exhaust.

[Fig 5.] How the “path” of the airflow is designed can decide whether a certain roasting machine do or do not have a “dead zone”.

Balanced flow velocity:

If the airflow is too weak, chaff lingers and burns. If it is too strong, beans themselves may be disrupted, lifting erratically inside the drum and stressing the motor. Effective design balances flow speed to be powerful enough to evacuate debris without destabilizing bean movement.

The (Simplified) History of Roasting Airflow Control

Airflow control has not always been the fine-tuned process that many modern roasters take for granted today. The technology has evolved in clear stages:

No control at all:

In early drum roasters of the 19th and early 20th centuries, airflow was essentially fixed. Ventilation relied on basic fans or natural draft through chimneys. The focus then was simply: keep the smoke moving out of the workspace.

[Fig 6.] Whether on your kitchen stovetop or over the bonfire at a traditional Ethiopian coffee ceremony, there are no signs of forced ventilation methods in play. Photo excerpted from 93coffee website & Gillies Coffee website.

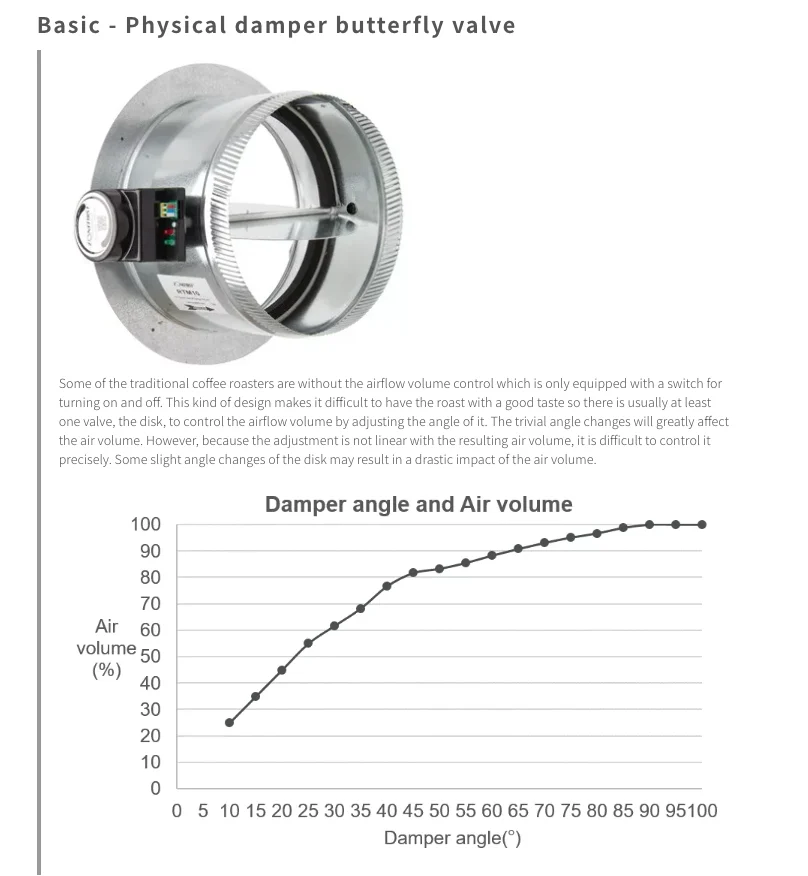

Introduction of dampers:

Later machines introduced mechanical dampers—physical plates or valves within the duct that could restrict or open airflow.

This was a big step because it gave roasters some immediate control, but adjustments were still crude. Air movement wasn’t linear and often lagged between input and effect, which made consistent profiling difficult.

[Fig 7.] Butterfly valve as the airflow control dampers are common designs on traditional drum roasters. Photo excerpted from Bideli official website.

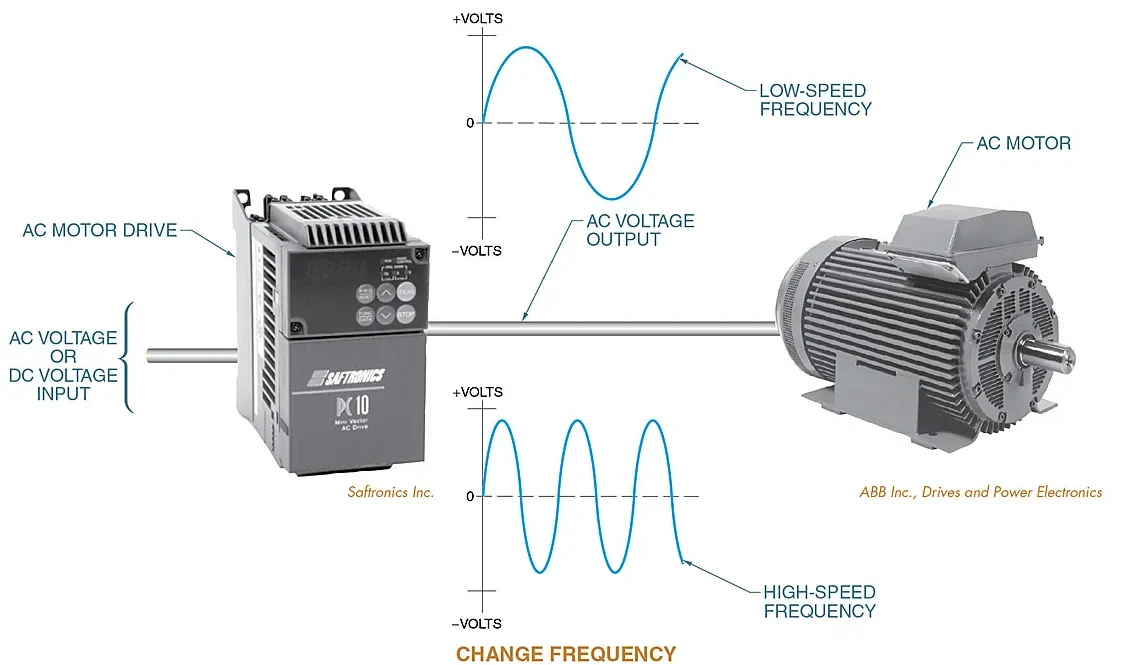

Variable frequency drives (VFDs):

As electric and industrial control technology advanced, fans could be powered by motors controlled via VFDs. This gave roasters the ability to finely adjust fan speed across a wide range in real time. With this came the possibility of treating airflow as a roast parameter that could be profiled, rather than just an on/off control.

[Fig 8.] By varying the frequency of AC electric currents that powers the AC motor, we can precisely control the spinning rate (rpm) of the motor. Photo excerpted from Electrical A2Z website.

However, the major issue with VFD-driven AC motors is that it cannot maintain identical spinning rates under varying loads. This means that when the pipings for the roaster starts to clog and induce a “back pressure” that changes the load on the exhaust fan motor, the amount of airflow will vary even if the exhaust fan control setting is the same, lessening roast control precision.

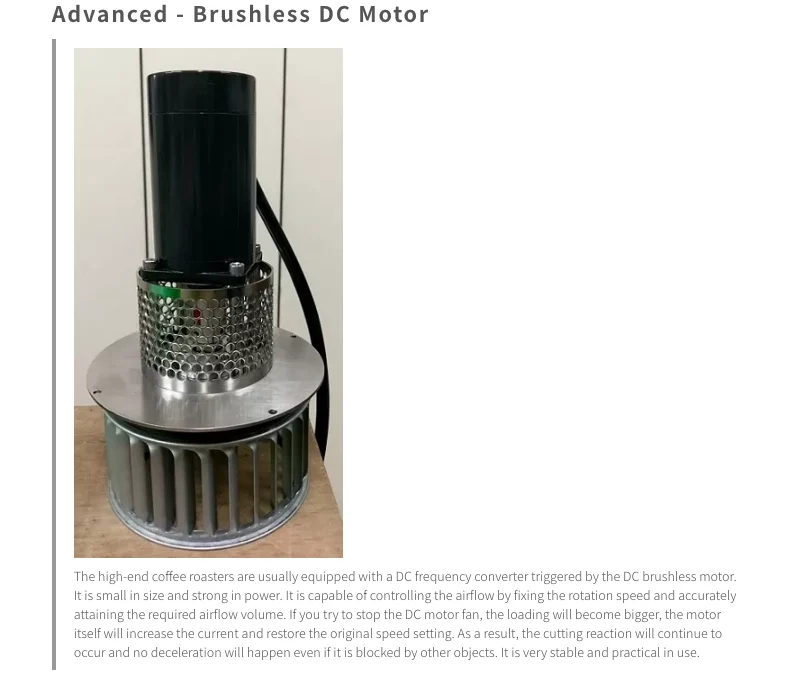

Modern brushless DC motors:

The newest generation of roasters, especially specialty-focused machines, employs brushless DC motors.

[Fig 9.] A brushless DC motor used for precise exhaust airflow control on a Rubasse NIR roasting machine.

Unlike traditional motors, these keep fan speed steady even as system back pressure changes — such as when chaff collects or more beans fill the drum. This ensures stability and repeatability, removing a common variable that once required constant monitoring.

Instagram Reels to showcase the linear airflow control ability of brushless DC motors.

From a technological perspective, airflow control has gone from being an afterthought to being one of the most precise and controllable variables in roasting.

“Controlling Convection?” – How Airflow Affects the Cup

Once debris and smoke are properly managed, airflow becomes part of your flavor toolkit. Adjustments influence the coffee’s balance of acidity, sweetness, clarity, and body.

Higher airflow:

Pulls heat more efficiently across the bean surface through convection. This can lead to cleaner, brighter cups with more pronounced acidity, since smoke is removed effectively and the roast environment is less heavy with particulate matter. However, if airflow is set too high without enough heat energy in the system, it can flatten sweetness or cause underdevelopment by cooling the beans prematurely.

Lower airflow:

Retains more heat within the drum and increases conductive influence. This often produces heavier-bodied coffees with deeper, more caramelized notes. The trade-off is that reduced airflow allows more smoke to linger, which can dull clarity and, if taken too far, introduce unwanted bitter or ashy tones.

- [Fig 10.] The airflow adjustment damper on a traditional drum roasting machine (the probat UG series) has several different settings marked with the words “Expresso, Extern, & Aroma”, implying that different airflow characteristics do have a significant effect on the sensory qualities of roasted coffee. Photo excerpted from Probat’s official Instagram post https://www.instagram.com/reel/C22sJZKx24C/

Balancing airflow-to-power ratio:

Airflow should always be understood relative to the amount of burner or power input being applied.

If the airflow is too low for a given level of heat, air temperatures inside the drum can spike, raising the risk of scorching, tipping, or excessive radiant heating from overheated metal surfaces.

On the other hand, if airflow is too high while power is held constant, you may dilute the air’s thermal energy and slow down the roast’s chemical progress.

Counterintuitively, this can shift more of the heat transfer burden back onto the drum walls, effectively increasing conduction while reducing the intended role of convection. Inconsistent results often come from failing to match airflow to the heat available in the system.

Practical Scenarios – Managing Airflow-to-Power Ratio for Different Kinds of coffees

The balance between airflow and power is not a theoretical concern — it plays out differently depending on the bean’s density, processing style, and intended roast profile.

Two common examples highlight how roasters think about this ratio in practice:

High-density washed Ethiopian:

These coffees, grown at higher elevations, usually have compact cell structures that demand steady, strong energy input to drive heat into the bean’s core.

For this type of coffee:

- Roasters often pair moderate-to-higher airflow with strong burner input in the early stages. The airflow helps carry heat uniformly across the beans and prevents localized scorching from the drum walls, while the robust flame ensures that the air itself is hot enough to sustain effective convection.

- If airflow is cut too low at high power, the thin beans can easily tip or scorch due to overheated drum metal. Conversely, if airflow is too high without enough flame, you risk diluting the environment, slowing chemical reactions, and stretching the roast in ways that flatten the coffee’s floral complexity.

- A balanced approach ensures the coffee develops clarity and high-toned aromatics that washed Ethiopians are celebrated for.

Lower-density natural Brazilian:

Natural-processed Brazils are more porous and less dense, requiring gentler energy delivery to avoid overdevelopment or “baked” flavors.

For these beans:

- Roasters often dial back airflow and power together, especially during the mid-to-late roast. Lower airflow lets the beans absorb conductive heat smoothly without overly accelerating the roast, while controlled burner input avoids spiking drum temperatures.

- If airflow is too low while power remains even modestly high, the thin skins and porous structure of these beans make them vulnerable to tipping or uneven surface burns. Too much airflow without enough flame, on the other hand, can sap sweetness—resulting in a thinner, flatter cup.

- The right balance leans toward richer body and chocolate-toned sweetness while keeping a stable roast environment that doesn’t strip away the subtle dried-fruit notes common in naturals.

In both scenarios, the principle remains: airflow without sufficient heat weakens convective development, while heat without sufficient airflow creates dangerous localized stress.

Calibrating the two together is what protects coffee’s character — whether you want to highlight sparkling florals in a washed African or deepen layered sweetness in an easy-drinking natural Brazilian.

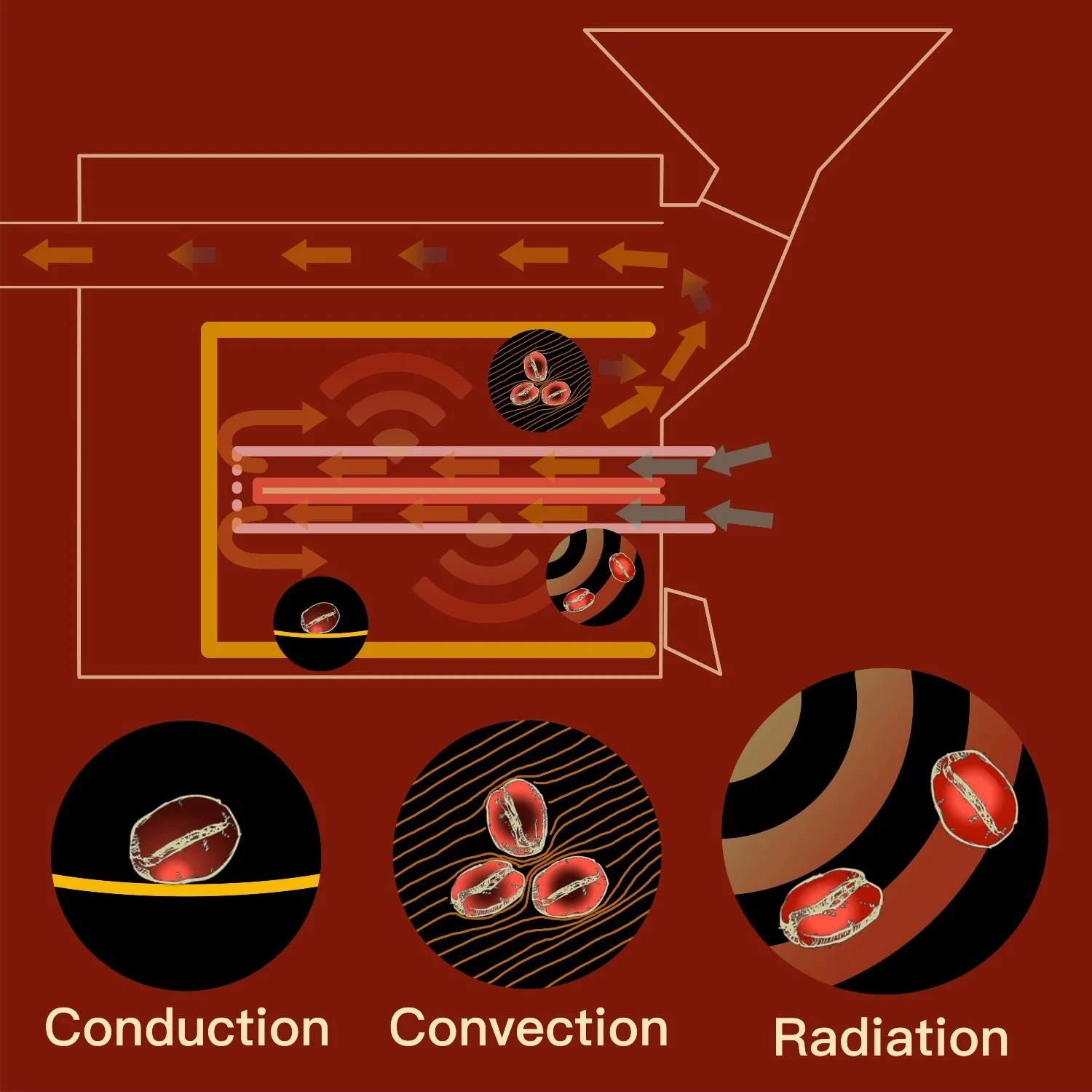

Keeping Airflow Truly Consistent – Manometers and Differential Pressure Gauges

One common mistake is assuming that identical fan settings (for example, “40% fan speed”) always equal identical airflow.

In reality, roast environments change: exhaust ducts gather oil and chaff, ambient conditions shift, or filters become partially blocked. Each of these factors can reduce the actual flow moving through the drum — even if the fan is running at the same setpoint.

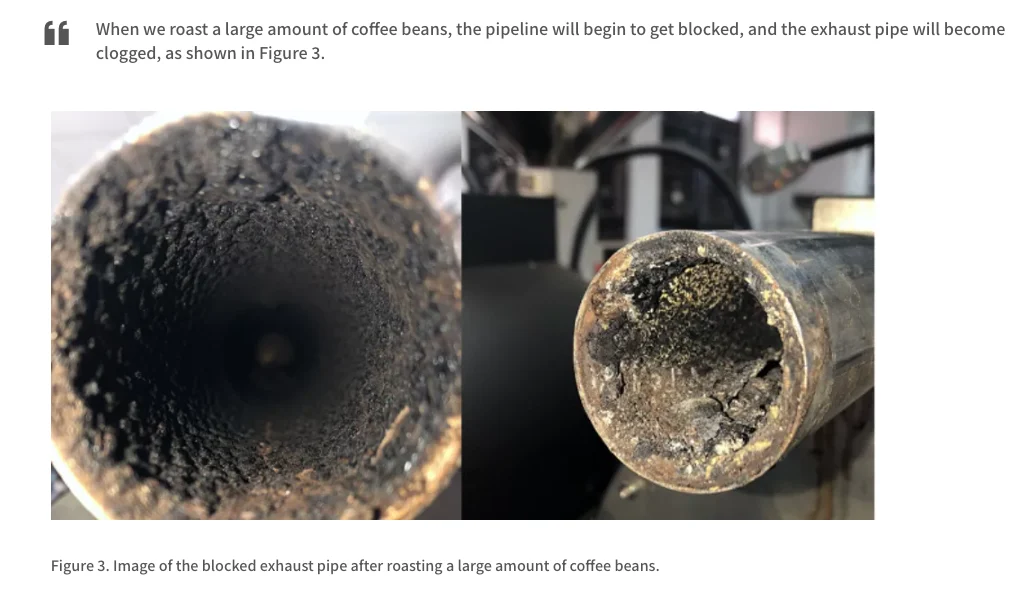

[Fig 11.] Debris, char, and chaff accumulated in the exhaust pipes on a roasting machine. As the picture shows, if neglected, the build up amount can actually reach intimidating levels that may even cause overheating & fire hazards.

This is where differential pressure monitoring becomes crucial.

By installing a manometer or differential pressure gauge across the drum or exhaust system, roasters can directly measure the volume of air being drawn through the chamber.

[Fig 12.] Even when using traditional airflow dampers, drum roasters nowadays also included a manometer that enables roasters to adjust the damper manually according to the differential pressure data.

Instead of trusting a fan dial, the roaster sees a real-time indicator of how much resistance or back pressure is present in the system.

- Over time, a gauge reading that trends upward signals obstruction or buildup in exhaust pathways.

- Maintaining target pressure readings batch after batch helps ensure airflow conditions remain stable across different roast days.

- This consistency allows roasters to better replicate roast curves and confidently attribute changes in the cup to intentional adjustments, not hidden ventilation variables.

For precision-focused roasting, a manometer isn’t a luxury — it’s one of the few instruments that ensures the “invisible” variable of airflow remains quantifiable and repeatable, even as the roaster ages or conditions change.

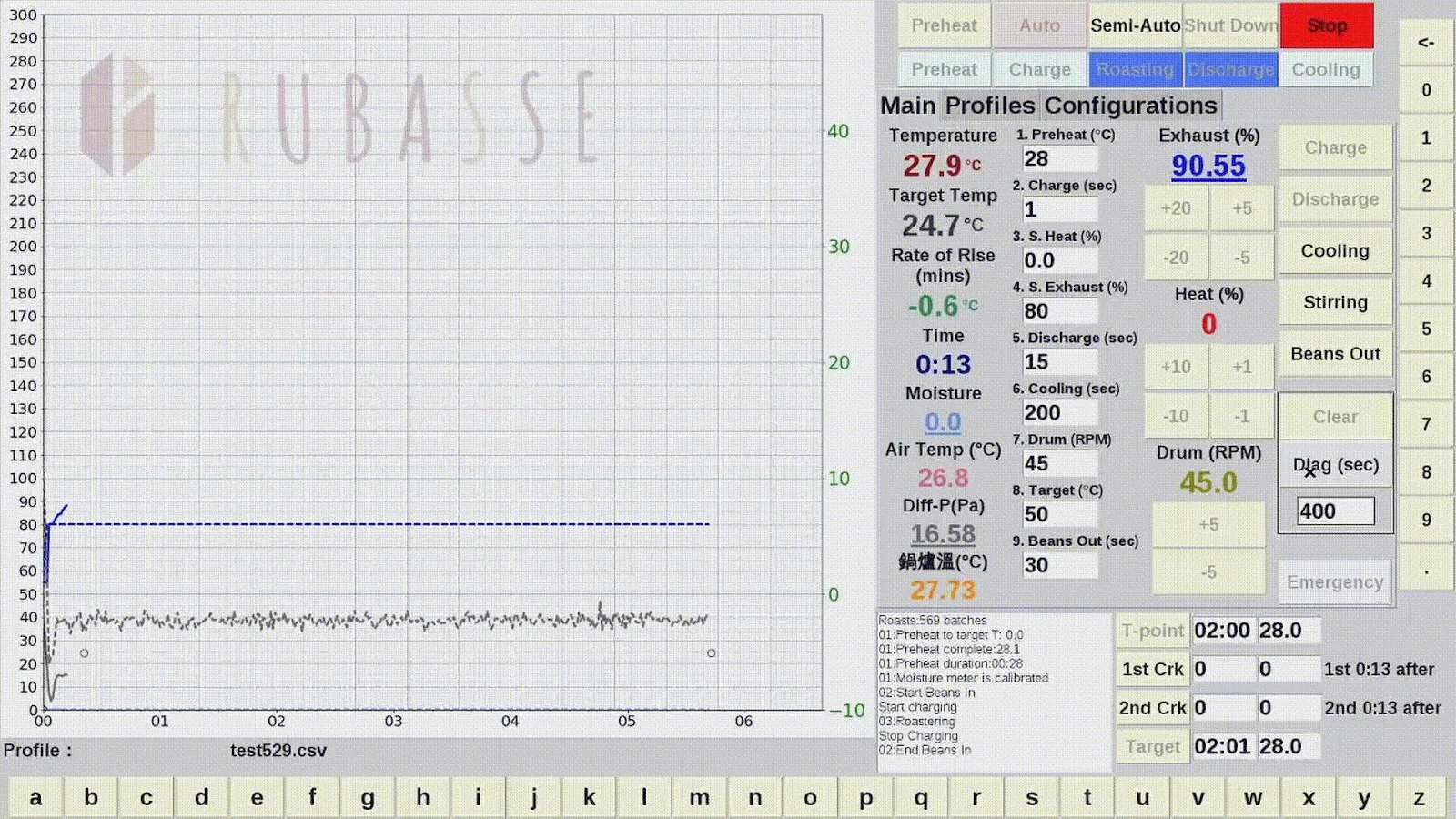

Also, the use of digital manometers paired with digitally controllable airflow adjusting mechanics also makes automatically maintaining certain pre-programmed differential pressure values across a roast possible, as shown in the graph below.

[Fig 13.] The “Differential Pressure Compensation system” at work on a Rubasse Micro 3kg roasting machine. The exhaust control is automatically adjusted by a microcomputer in order to gain the desired differential pressure and airflow condition within the roasting drum.

If you want to learn more about “differential pressure compensation” during roasting, you can kindly take a look at this linked article.

Ending Words

Airflow is one of the most powerful yet often overlooked tools in coffee roasting.

When managed thoughtfully — and in balance with heat — it not only keeps the roasting environment clean but also shapes sweetness, clarity, and body in the cup.

Understanding and controlling it with precision is what elevates a good roast into a consistently great one.