When coffee is being roasted, it loses moisture, increases in temperature, changes color, and starts chemical reactions that create the magical flavor developments (until you decide to rapidly cool the beans & stop most of those reactions) – All of this is driven by the energy applied onto the coffee beans in the form of “heat”.

So, it is safe to say that if you master heat transfer, you’ve already mastered coffee roasting at its essential core.

During the process, the roasting machine is simply just the tool for you to perform the necessary heat transfer needed, but like the saying “different tools for different tasks”, depending on your desired results, the “type” of tool (roaster) you use can affect the ease for you to reach your goals.

So if the goal for us is to roast tasty coffee and choose a machine that can help us do so, we have to tackle 2 problems in order to get the results we want :

- What are the basics of heat transfer?

- How do these heat transfer methods actually work under a coffee roasting scenario?

So for now, without further ado, let’s start digging in.

Prelude: The 3 Different Heat Transfer Principles

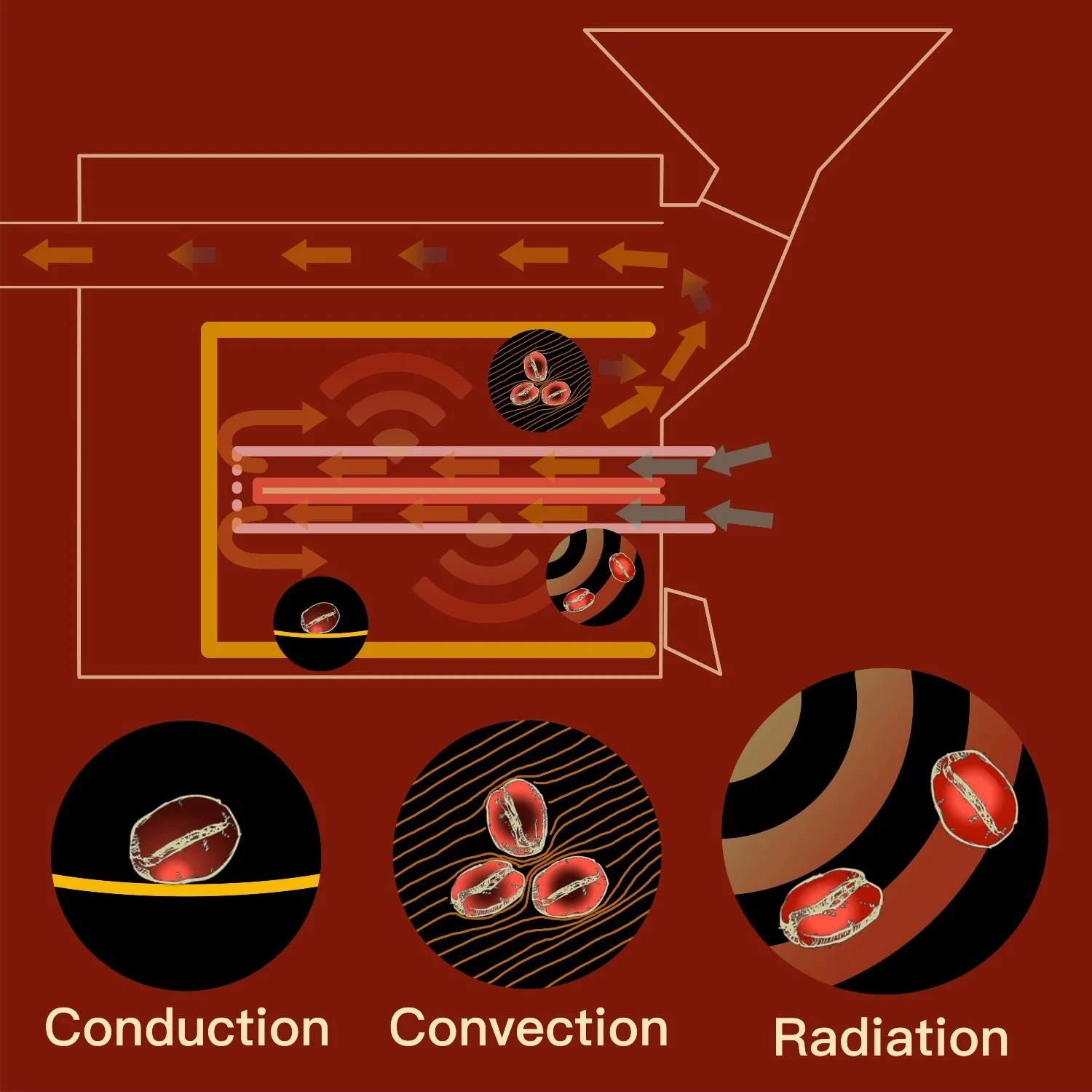

Physics tells us there are 3 modes of heat transfer: Conduction, Convection, & Radiation.

All 3 modes will all be at work when coffee is being roasted in any roasting machine.

However, inside each machine, there will be differences in “the ratio of the 3 modes of heat transfer methods” – and this difference is the main reason that we have different “types of coffee roasters” that “create different styles of coffee”.

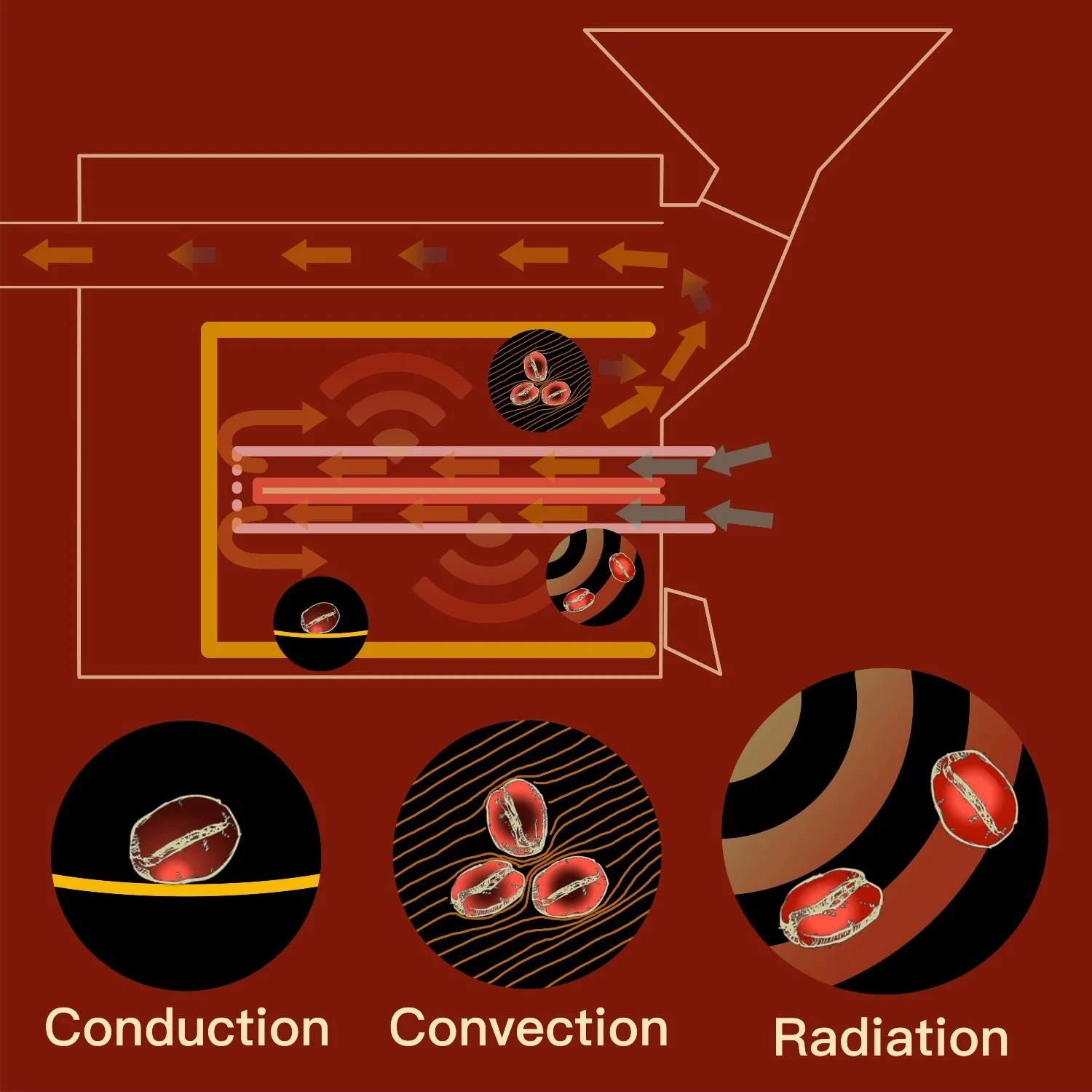

Below is a graph of an imagined, typical coffee roasting machine internal environment sketch while some beans are being roasted.

[ fig. 1. ] As shown, all 3 kinds of heat transfer modes will be at work when a batch of coffee beans is being roasted in a cutting-edge “radiation-driven” coffee roaster. Note the different “patterns of heating” as demonstrated by the red colors.

As illustrated, all 3 heat transfer modes are at work.

Now we will start to dive deeper into each individual mode of heat transfer. For each of the 3, we will:

- First, talk about its basic characteristics;

- Second, give prominent example(s) of roasting machines that showcase clear characteristics of this particular heat transfer method;

- Third, using the roasting machine as an example, we talk about how this particular heat transfer method can affect the roasting process and/or the final coffee’s flavor.

1- Conduction:

Heat transfer by conduction happens when a hotter object passes its energy directly onto a cooler one through physical contact. Picture laying a steak onto a searing hot cast iron skillet: the surface touching the metal browns quickly, creating that delicious crust.

Coffee beans experience something similar inside a roaster.

When they come into contact with a hot drum wall or another heated surface (such as the face plate of the roaster), conduction delivers energy directly into the bean. This can intensify sweetness, deepen caramelization, and build a rich body in the cup.

At its best, conduction creates complexity and roundness. But if the contact is uneven or excessive, the roast can become scorched — resulting in a charred exterior, smoky notes, or ashy flavors that overpower the subtler aromatics inside the bean.

Examples for conduction-based roasting machines:

- the Aillio Bullet R1,

- Traditional drum roasters (when operated in a way that heats up the drum excessively),

[ fig. 2. ] The Aillio Bullet R1, a prominent example of conduction-heavy coffee roaster. Photo excerpted from Sweet Maria’s website.

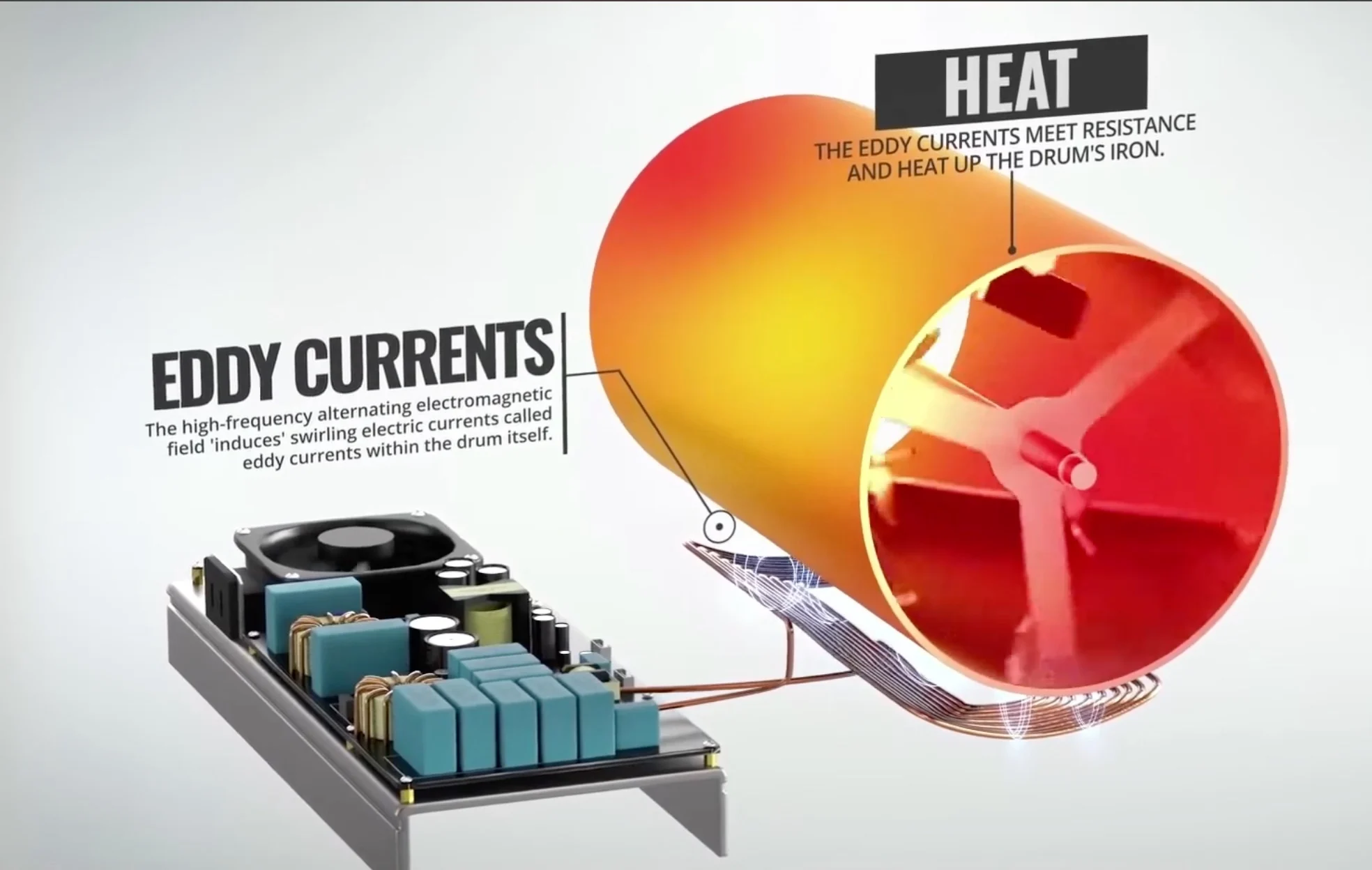

One great example of a conduction-heavy roasting system is the Aillio Bullet R1.

Unlike traditional gas-powered drum roasters that drive much of their heat transfer through convection (hot air circulation), the Bullet uses an induction heating system, as shown in Aillio’s official induction heating introductory video below:

The induction coil rapidly energizes the drum itself, making the metal surface the primary heat source for the beans. In practice, this means the primary and majority of roasting energy comes from direct contact between the beans and the hot drum wall.

[ fig. 3. ] The induction coil system in the Aillio Bullet R1, heats up the drums first and foremost during roasting. Photo excerpted from the YouTube video https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pLHY7x4yLUM

Another common example of a conduction-heavy roasting system is a traditional drum roaster that’s operated in a way that heats up the drum excessively.

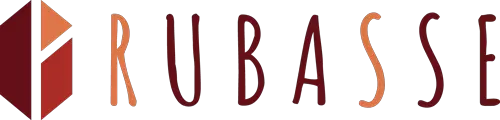

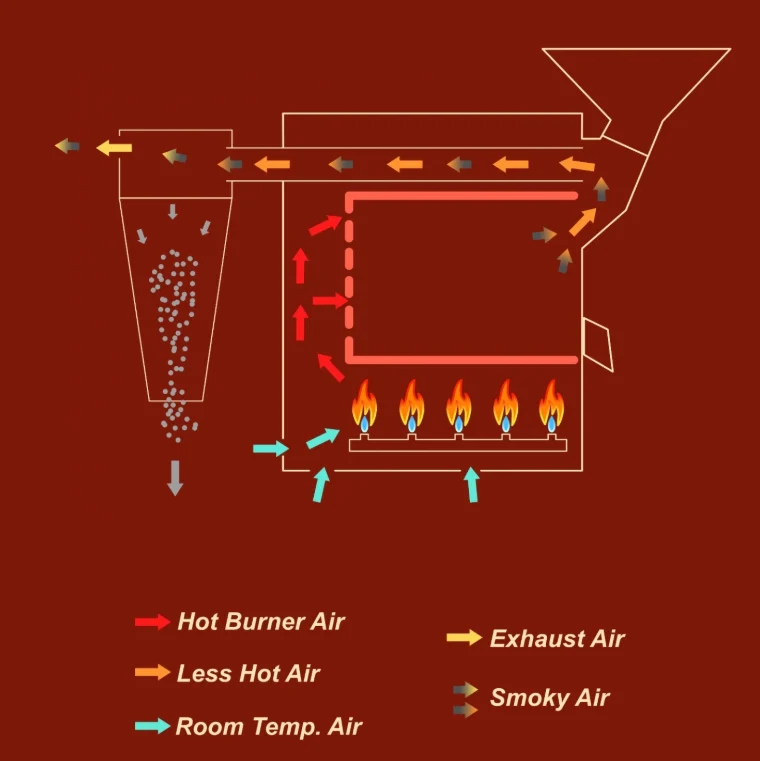

As the below graph illustrates, most traditional drum roasters have an open flame heat source that is directly in contact with the roasting drum, often “over-heating” the metal.

Now pair this over-heated drum with roasting air that has lower temperatures (possibly due to excessive airflow), and you end up with a roasting environment that is also highly conductive.

[ fig. 4. ] A drum roaster with open flame directly in contact with the roasting drum, potentially overheating it and increasing the ratio of conductive heat transfer.

This kind of “conduction dominant” design offers both advantages and challenges.

On one hand, conduction-dominant roasting can produce exceptional flavor intensity and a well-developed body when managed carefully.

On the other hand, because so much energy comes through conduction, operators must pay close attention to bean movement, drum speed, and batch size.

If airflow is too low or the beans linger against the hot wall for too long, there’s a higher risk of tipping (scorch marks) or burnt surface flavors resulting in ashy, smoky, or “brown and bland” cups.

For roasters, success with these “conduction dominant” machines often comes down to balance: learning to harness its rich, complex flavor potentials while still using airflow and agitation to distribute heat evenly.

Done right, it can unlock surprisingly sweet, syrupy cups with strong caramelization, while still preserving some of the bean’s inherent flavors, making the cup familiar enough for non-specialty coffee drinkers but still showcasing what specialty coffee can be through the delicate nuances that’s under the sweet, warming coffee notes.

However, if you want to showcase the full potential of the coffee beans inherent qualities WITHOUT masking it with much over-powering caramelization flavors, you might want to take a look at the next heat transfer mode for coffee roasting: convection.

2- Convection:

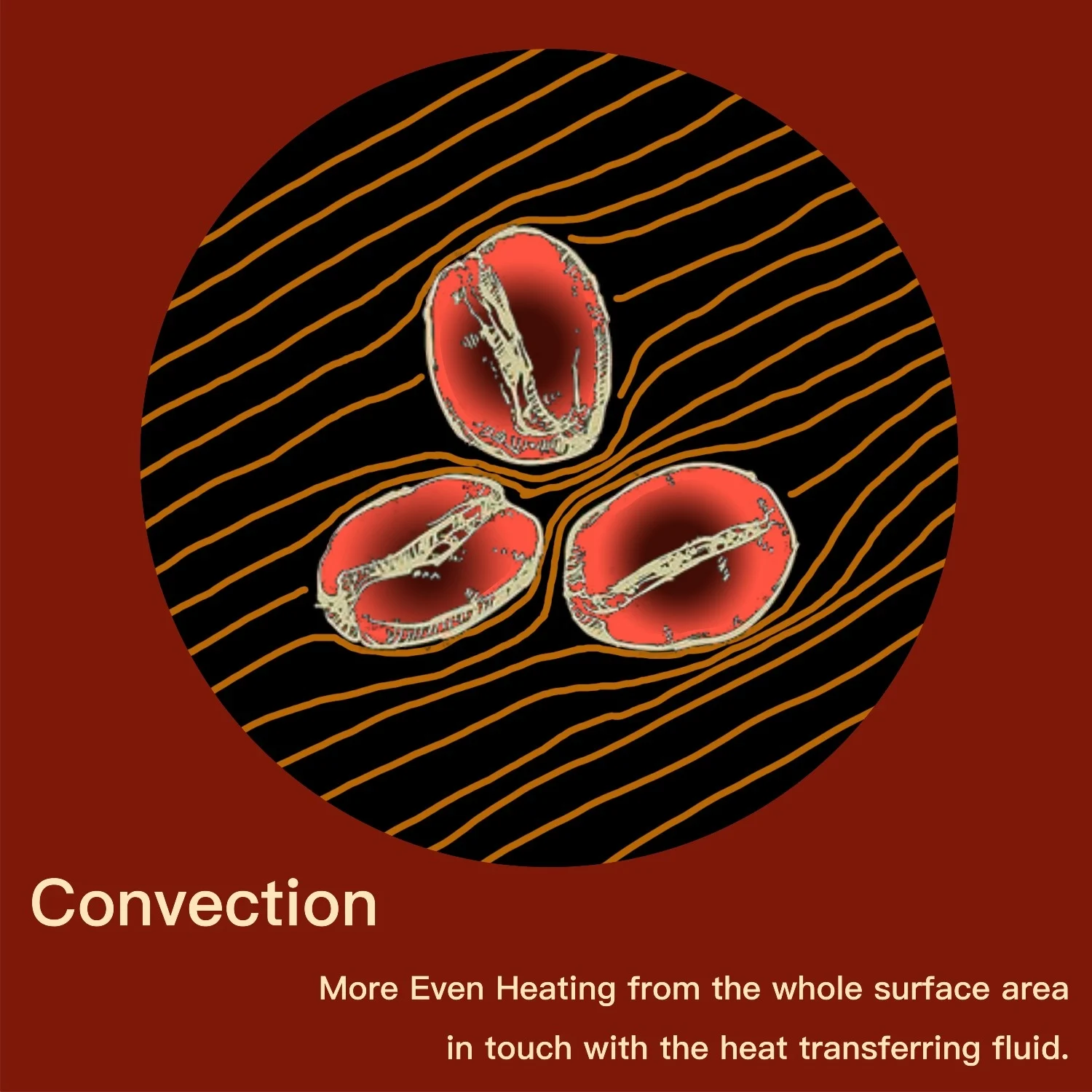

Convective heating occurs when heat is transferred by a moving fluid — most commonly hot air or water — to another object.

The efficiency of the heat transfer process depends on two main factors:

1. “Temperature difference” between the fluid and the object being heated. The greater the difference, the more heat is transferred.

2. “Flow speed” of the fluid across the object. Faster-moving air or water transfers more heat, even if temperature remains constant.

Think of sitting in a hot tub already at the edge of comfort. When you sit still, the heat feels intense but steady. Now, start waving your arms and legs — the sensation of burning increases, not because the water is hotter, but because fresh hot water is constantly flowing across your skin, transferring more energy.

In coffee roasting, the “fluid” at work is hot air. Convection drives heat evenly across the beans as they tumble in the chamber, enveloping each one in a flow of heated air. Compared with conduction, which only heats tiny contact spots when a bean touches the drum wall, convection allows the entire bean surface to be bathed in a consistent flow of energy. This makes air-based heating more even, effective, and efficient.

Examples for convection-based roasting machines:

- Loring smart roasters

- Sivetz fluid-bed roasters

[ fig. 5. ] Left: The Loring S35 & Right: The renewed Sivetz 15kg fluid bed roaster, both pioneers and marked milestones of the coffee roasting machine manufacturing history. Photo shot by the author and excerpted from Sivetz’s official website.

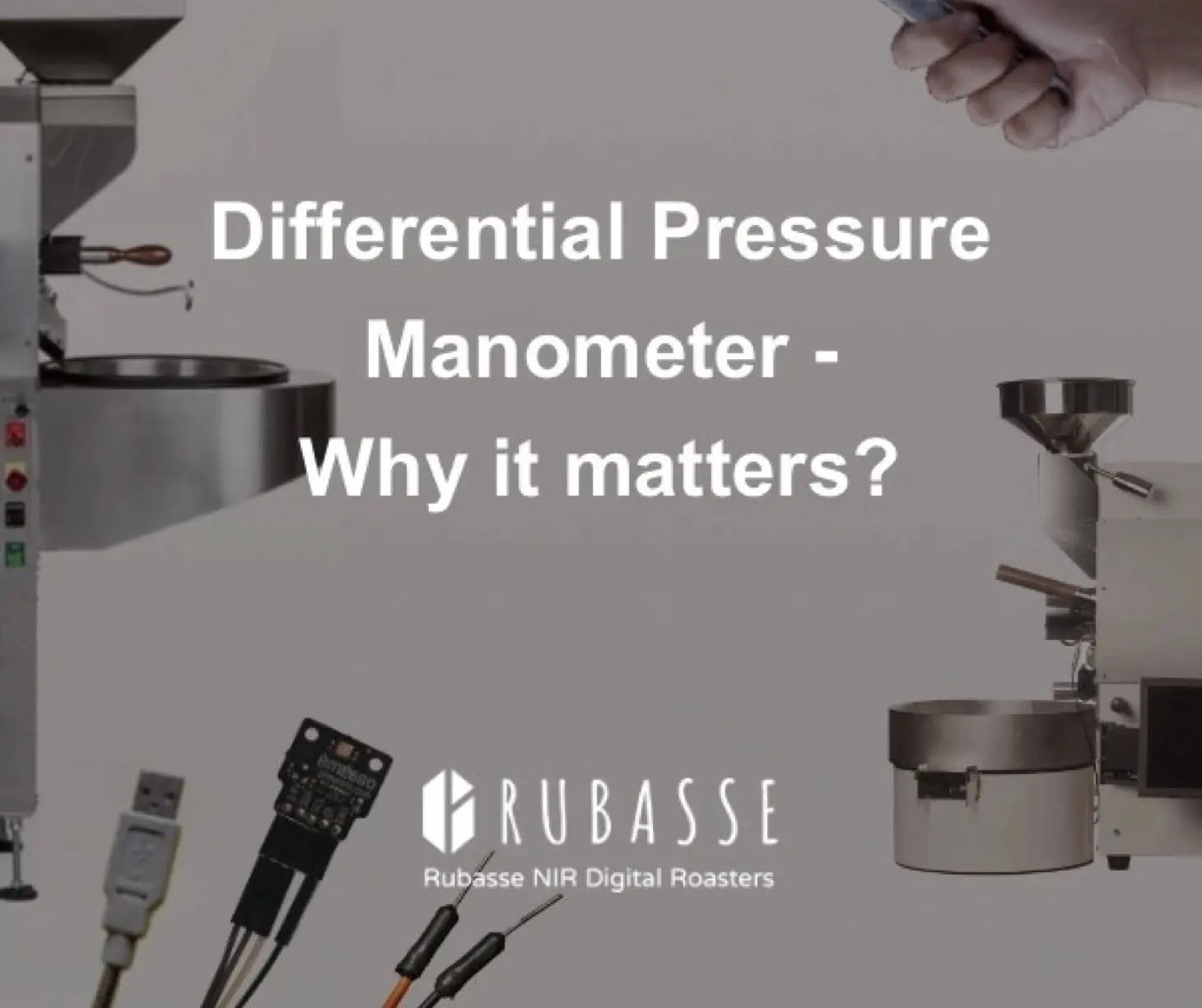

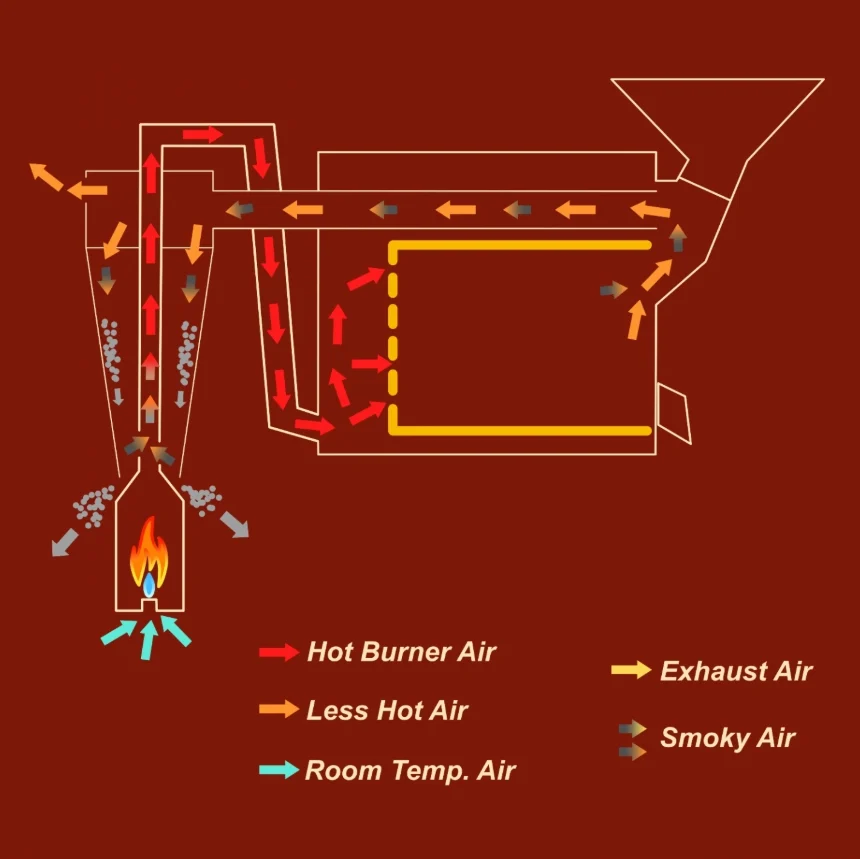

Loring Smart Roasters uses a highly efficient design where heated air is forcefully circulated through the bean mass.

[ fig. 6. ] Schematic diagram of a Loring roaster’s heating design. Note the “recirculation” of the airflow, which is one of the major differences this roasting machine holds in comparison to other drum roasters.

Instead of burners heating a metal drum directly, the Loring channels air through a single burner system, recycling exhaust gases for both energy efficiency and extremely stable airflow. This makes convection the dominant heat driver. The result is clean, even heat transfer with reduced risk of scorching, producing cups that often highlight clarity, acidity, and delicate aromatic notes — qualities that can be muted in more conduction-heavy roasts.

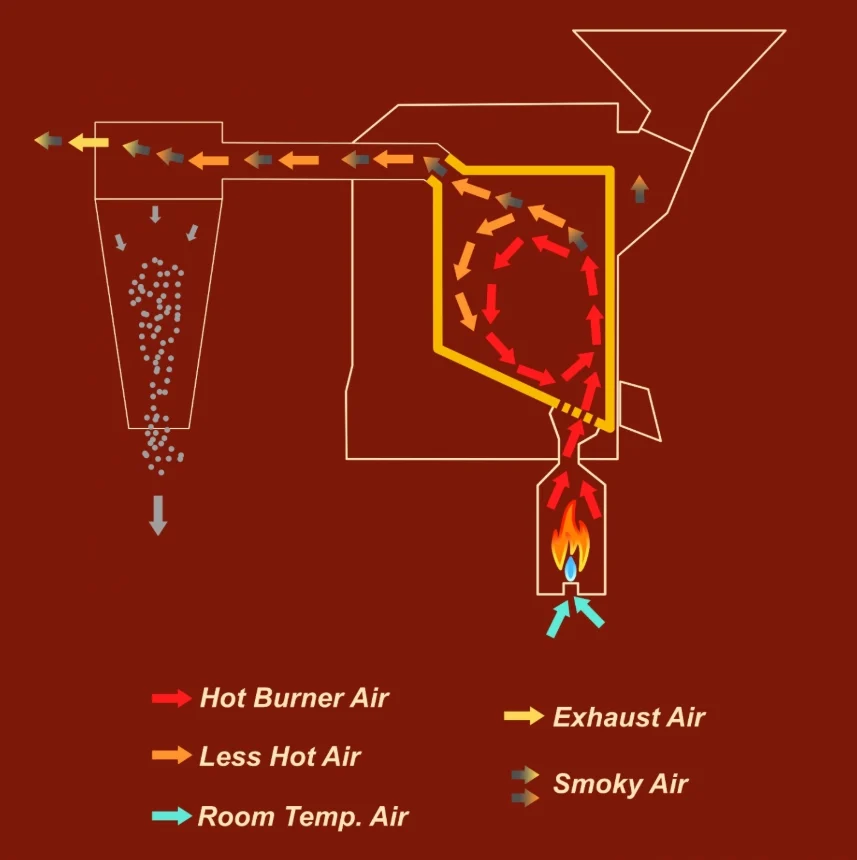

The Sivetz air roaster, an earlier pioneer of fluid-bed roasting, takes convection to its extreme.

In this system, beans are literally suspended or “floated” in a column of hot, rapidly moving air. Because the beans are not in direct contact with metal surfaces, almost all heat transfer comes from convection. This method promotes exceptionally even surface heating, yielding bright, lively cups with pronounced aromatics.

[ fig. 7. ] Schematic diagram of a common fluid bed roaster’s (such as the Sivetz machines) heating design.

The challenge, however, is controlling development:

Because the beans are suspended and agitated by a strong stream of hot air, there is a practical lower limit to how little airflow can be used during a roast.

In the later stages, when beans are lighter, more fragile, and increasingly sensitive to heat, the sheer volume of hot air required to keep them moving can push energy into the beans too aggressively. This can drive rapid roast development and lead to harsh, overcooked flavors.

Managing the finishing phase of a fluid-bed roast often requires exceptional precision, since even slight adjustments to air temperature or flow can produce amplified effects on the final flavor quality.

Both Loring and Sivetz roasters demonstrate the power and potential of convection as a heat transfer method. By enveloping the beans in streams of carefully controlled hot air, they create conditions that are efficient, even, and capable of revealing unique flavor signatures—emphasizing clarity, brightness, and aromatic complexity.

Still, no system is without tradeoffs.

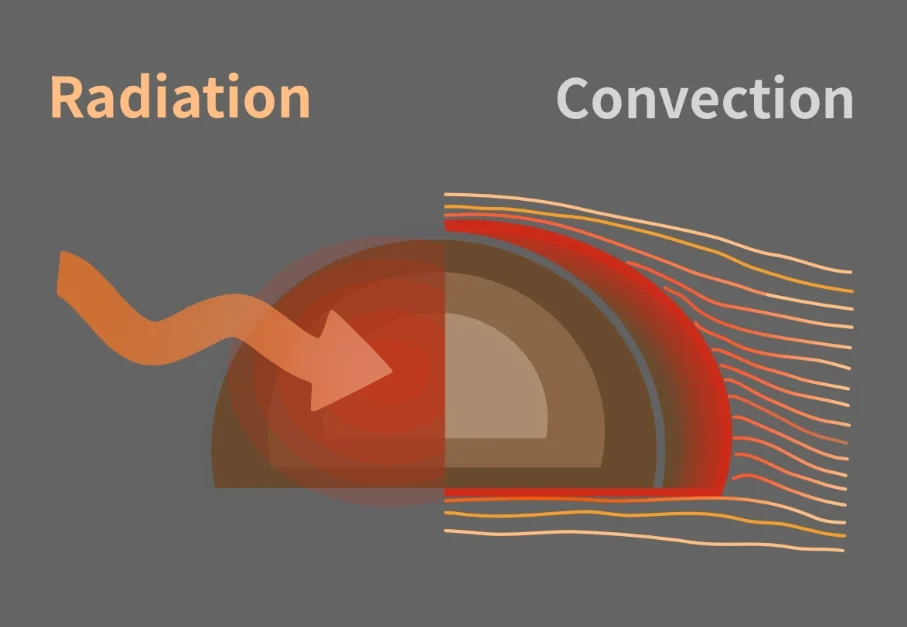

Although efficient and even in heat application, convection still acts on the bean surface first. It takes time for heat to diffuse inward to the core of the bean.

This makes control of timing and airflow critical — roasters need to carefully balance air temperature and roast tempo to ensure beans develop evenly from outside to inside without drying out or tipping too fast. This often means countless hours of trial-and-error before finally settling on something that fits the expectations.

Also, convective roasting tends to require higher energy input compared to other methods, especially when maintaining the continuous airflow needed for stability and consistency. This results in increased energy demands and, in some cases, higher operating costs.

To address this, modern approaches often explore hybrid heat transfer methods as a way to reduce energy consumption while still achieving balanced, high-quality roast results.

This naturally brings us to the last, and perhaps most intriguing, mode of heat transfer: radiation.

3- Radiation:

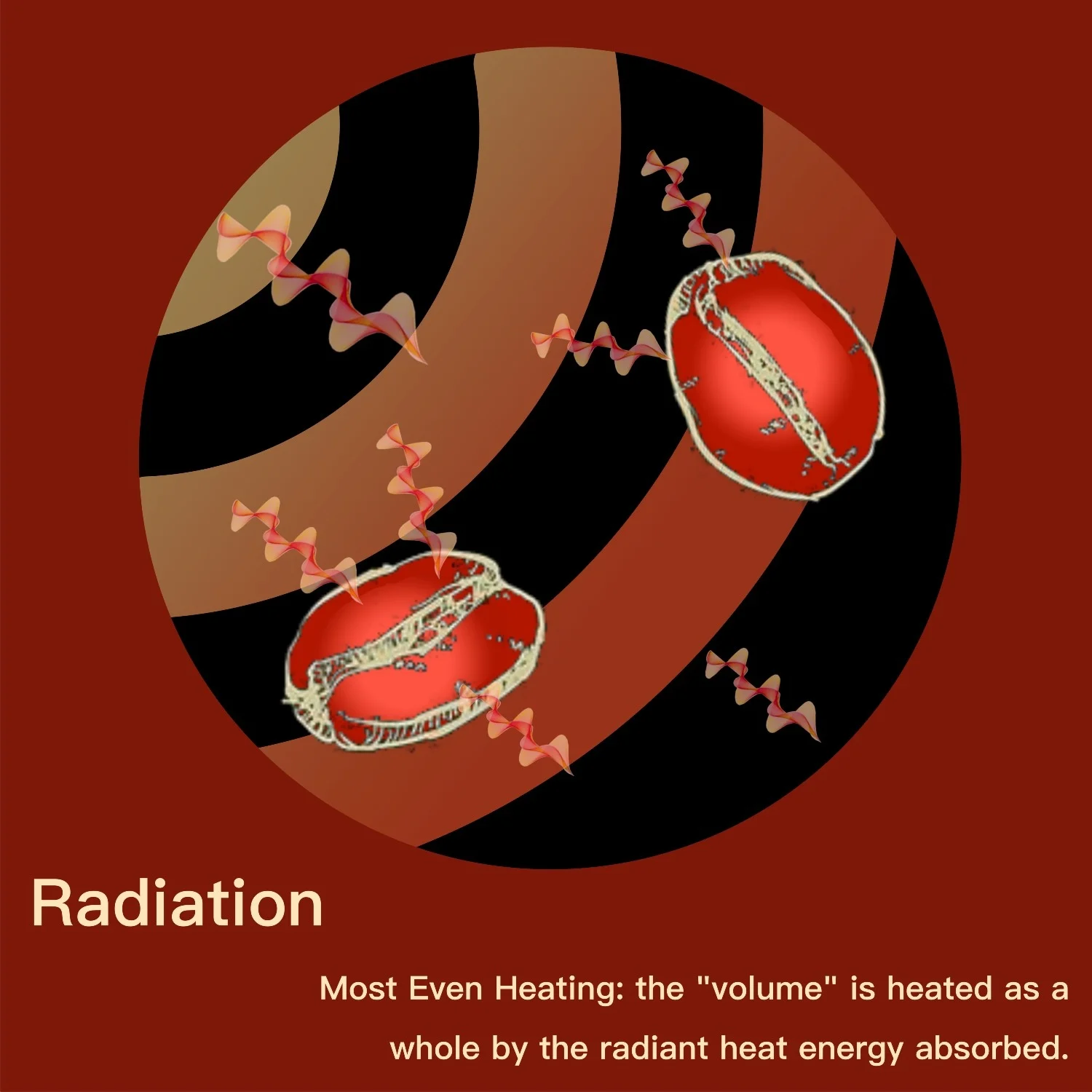

Radiation heating uses energy transferred by electromagnetic waves that can travel through empty space without the need for any physical medium like air or metal. When these waves strike an object, some energy is absorbed and increases the object’s temperature, some is reflected, and some may pass through. The absorbed portion is what actively raises the temperature of the object being heated (roasted).

Though the use of deliberate radiant heat sources is a recent innovation among coffee roasting machine manufacturers, radiation has quietly influenced roasting for decades. Both open flames and heated drums in traditional roasters emit a measure of radiant energy, imparting subtle (and not-so-subtle) effects on bean development.

[ Fig. 8. ] For example, direct-fire roasters allowradiant heat from the flame to pass through the holes and grooves on the drum and strike the beans directly, diversifying the roasting heat transfer method and contributing to a distinct roasting style. Photo excerpted from Home Barista forums.

Radiation has some distinct advantages:

- It doesn’t require any medium to transfer heat, so it can be extremely efficient compared to conduction or convection.

- Radiation can penetrate deeper into the beans, speeding up core heating and making the process remarkably effective — even more so than convection, which only heats the bean surface initially.

[ Fig. 9. ] Radiant heat is evenly absorbed by the total mass of a coffee bean, while convective heat is mainly & firstly absorbed by the outer surface of a coffee bean. Roasting with radiation means: 1. Faster roast development (especially as the beans get darker) and 2. Less uneven and/or prolonged “baked” roasts.

Inspired by these benefits, several leading manufacturers have pursued dedicated radiant roasting designs. Among them, the Rubasse NIR Digital Roaster stands out as a prime example.

Radiation in the Rubasse NIR Roaster

Rubasse roasters use patented near-infrared (NIR) heating elements located at the center of the drum, emitting radiation energy within wavelengths of 750–1500 nm.

These NIR waves are carefully chosen because coffee beans and grains absorb them exceptionally well, leading to rapid, ultra-responsive heating.

The Rubasse NIR roaster maximizes energy efficiency by creating a resonant “optical cavity” within the drum. Here, radiant heat not only directly heats the coffee beans, but is also repeatedly reflected and absorbed by the beans, drum wall, and air inside the chamber.

[ fig. 10. ] Radiation does not heat up air directly. Instead, the near infrared radiant energy would: 1. Be absorbed by the coffee & be used for roasting directly; 2. Transmit through the bean, and be reflected by the drum inner surface; 3. Absorbed to heat up the drum.

This structure ensures minimal energy loss and high thermal efficiency, supporting back-to-back roasting while keeping drum temperatures stable and preventing component overheating. Roasters can finely adjust heat output via precise touch controls, leading to highly controllable, repeatable roast profiles—even when roasting full batches.

Another key feature is consistent and deep penetration of heat. NIR radiation can reach up to 1 cm into the bean, helping both the surface and core to develop evenly and swiftly. This means flavors are revealed with striking clarity and vibrancy, resulting in exceptionally clean and bright cups.

Ending Words

Taste in coffee is deeply personal—what delights one person’s palate might leave another unimpressed. Yet, underneath every flavor journey lies the physics of heat transfer. If certain “styles” or flavor profiles attract you, choosing a roasting machine with the right heat transfer nature isn’t just helpful—it’s essential. Trying to coax a clean, nuanced cup out of a conduction-heavy machine, or chase syrupy sweetness in a pure convection setup, will always be an uphill battle.

Ultimately, theory and preference can only take us so far. The real truth of any roasting method or machine is found in the cup itself. Experiment boldly: whenever curiosity strikes, don’t hesitate to try any roaster that inspires you. Only through firsthand experience—seeing, smelling, and finally tasting—will you discover what truly suits your tastes and roasting goals.

Every machine and heat transfer method offers a different path to flavor…so let your curiosity guide you, and let your cup decide.